At 111 Cannon Street is a piece of stone, or rock, but it’s not just any old piece of stone, this is the London Stone, something that has graced London in almost the same location for centuries and has had myths and stories grow around it’s mysterious past.

Since 2018 the London Stone has been back on Cannon Street after a short stay in the Museum Of London where it had been placed when it’s previous home was being demolished.

The first written references to the Stone date back to the early 12th century, and since then it’s always been in location close to the Walbrook River and in the 1820’s it was embedded into the wall of the Christopher Wren church of St Swithin’s. Here it stayed until the Blitz when the church was destroyed, clearly not the Stone though.

The Stone remained in situ in a wall left standing by the damage through until the 1960’s when the remains of the Church were demolished and a new office block built, 111 Cannon Street. An enclosure for the Stone was designed to be built into the wall and that’s where it spent the next portion of it’s life for the next 50 years or so sitting behind an iron grill. Behind the enclosure for some time was a retail shop, and though the back of the Stone was generally hidden by racking at times it could be seen from inside the shop.

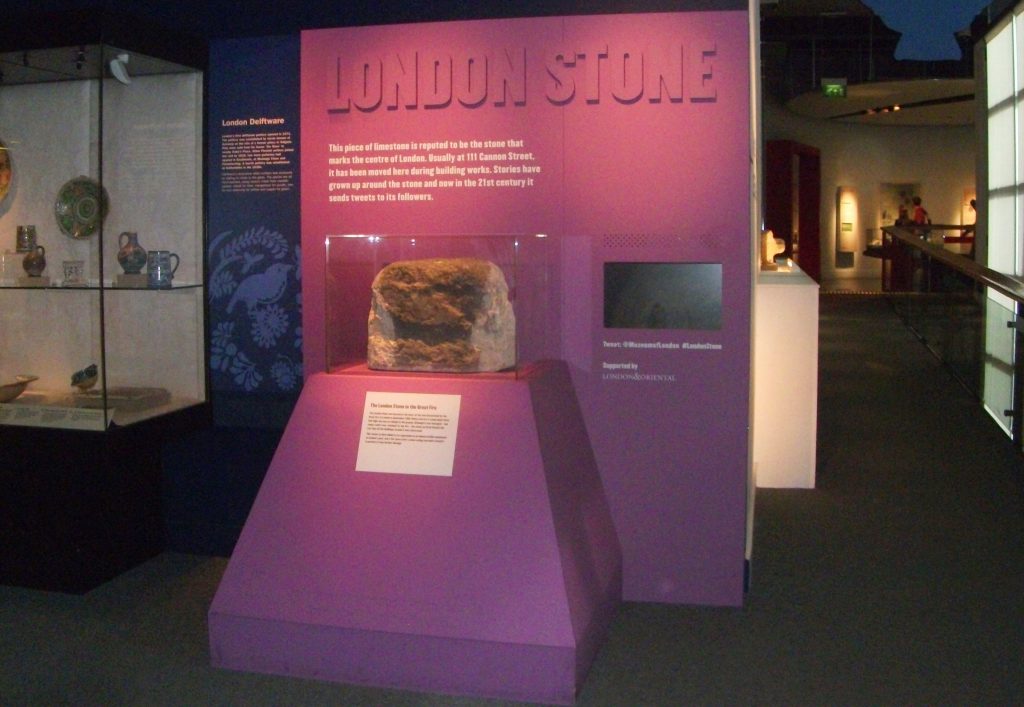

Fast forward to 2016 and the Stone moved for it’s brief stay in the Museum Of London while once more it’s home on Cannon Street was demolished and rebuilt, before, in 2018 it returned once more to a purpose built enclosure, this time behind glass and visible again from the pavement.

The London what?

So that’s the ‘where’, but how about the ‘what’? This is where things get a little more hazy.

Known as the Heart Of London the Stone has had a myriad of myths and stories spring up around it over the centuries and the truth is nobody really knows it’s origins though some theories are more likely than others.

Up until being placed in the wall at St Swithin’s we know that the stone stood in the centre of Candlewick, later to be Cannon Street and was a well known landmark and marked on maps of Elizabethan London. It seems likely it was moved a few yards from this location as more coaches and carriages were using the road.

There is a belief among some, which has prevailed for centuries that if the Stone is moved away from this location the future of London would be jeopardized. It’s actually a piece Oolitic limestone, of the type first brought to London during Roman times for building and statues. It’s thought it originates from Rutland though there are also suggestions it could have come from Bath. Either way, both Romans and Saxons were known to transport the stone in for building purposes.

Roman perhaps? Or maybe Trojan?

Because of the close location of the Stone to where the Governor’s Palace stood in Roman times there are suggestions that originally it could have been part of that building, or a feature in the courtyard or even the stone that was used to mark distances to London. All very plausible but it’s highly unlikely that we’ll ever know if any are correct.

There is also a story that Brutus, the founder of Britain brought the stone with him when he founded his City, either from his ancestral home of Troy or from his Italian home. Brutus being something of a mythical figure whom few believe actually existed, this one is perhaps more of an outside shot. A post about Brutus is due to be published shortly for those that may be interested.

There were also claims that it was originally a Druid altar used for sacrifice, seeing as this started in 1720 with an account by John Strype it seems more likely to be a sensational story to attract attention though, heathen worship and sacrifice as 18th Century click bait seems a more likely truth.

Another theory is that when King Alfred the Great rebuilt London in 886 that the Stone was used as a marker in the centre of a new layout of streets. Again possible, but again we’ll likely never know.

A Stone for rulers

Kings and Queens would visit the Stone to take control of London? This is a story often told, but one that is certainly the work of fiction and we can even place the fiction.

The reality is that Jack Cade, leader of the Kentish Rebellion against Henry VI entered London in 1450 and struck his sword against the London Stone declaring himself the ‘Lord Of This City’, however there was no precedence for this and most chroniclers of the time saw no significance in the action.

Enter a certain Mr Shakespear however, who recreated Cade’s deed in Henry VI pt 2 and suddenly we have an origin for the folklore.

‘So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe, so long will London flourish’

So goes the ancient saying, a saying so ancient we can trace it back to a Welsh clergyman in 1862 called Revd Richard Williams Morgan who almost without any doubt made up the saying in an article in the periodical Notes and Queries in 1862.

Sorry another myth debunked.

The truth is that we will never know the truth, but in the meantime if you’re in the area why not take a look at the London Stone yourself, and then decide which story calls most to you, maybe even create your own?